We visited a comprehensive health center that I will forever remember because of its spotless but rudimentary bathroom (a hole in the ground, all cemented and reeking of chlorine). Health center or hospital bathrooms are rarely that clean even though one would think they are.

Next to the health center is a school: girls in the morning and boys in the afternoon. The girls, all in their black dresses and white veils clumped around us – we were the excitement of the day. Katie was like the pied piper with at least thirty girls following her every move. I got to sit at a disk with Malika and Rahela and practice writing their and my name in neat little schoolbooks. The eagerness and energy of these girls make you feel a little better about Afghanistan’s future, assuming they get to continue their schooling beyond a few grades and are not married before they reach puberty.

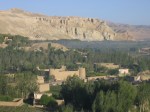

We followed the Community Health Supervisor to the house of a community health worker (male) in a small village outside the provincial capital, which itself is a small village. We were received in his father’s compound which he shares with his brothers and sisters and their offspring. He served us lunch which consisted of traditional bread, large bowls of yogurt with several spoons in each and plates with fresh butter. It was my kind of lunch, all dairy, only cheese missing. It was a feast in a poor man’s house and probably a considerable sacrifice.

Back in the provincial capital we visited the vaccination office and learned about how they manage the data flow and the multiple requests from everyone and his brother to see results. They have good results but the graphic representation of these didn’t really do their results justice.

Next we visited the provincial hospital where we met the nursing team that is working on lowering infection rates. I was happy to find a very smart and vocal nurse among the team with a great sense of humor. She belongs to a pool of female Aga Khan University (Karachi) alumns who I keep running into. They give me hope about Afghanistan’s future, if the men would only let them. She talked about the Taliban with irreverence and referred to it as a boring time. When we mentioned that we enjoyed our freedom here in Bamiyan and were somewhat constrained to office and house in Kabul, she quipped that now it was our turn to be Talibanned.

We toured the brand new maternity waiting home, a collaborative effort between the New Zealand Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT), local citizens who bought the land and UNICEF that will provide staffing. The lovely house, one long architectural curve sweeping around itself to come full circle (I was later told that it was designed by a Dutch (male) architect, engaged by UNICEF, who meant it to be shaped like a uterus.

The uterus building was just completed and awaiting its furnishings, equipment, water and electricity. Fifteen very pregnant women, each with a care taker, can lodge inside this uterine place until their baby arrives. This will free up the 15 hospital beds these women are now occupying. Such maternity waiting houses are being opened in other provinces as well. I was supposed to have witnessed one such opening in Badakhshan early March but the helicopter didn’t fly.

And finally we had a meeting with the provincial health team to digest our very full day. It was a complex meeting in that much was in Dari and I can follow about one third but not enough to really get myself understood well; things get lost in translation. I still have to mull over what our conclusions were and what we can and cannot do here in Bamiyan. Lots of opportunities and lots of constraints. More about this later. Photos also later. Katie has a real camera and is making awesome pictures.

Recent Comments