The weather has turned back towards winter again. It has been raining for the last few days and the warm summer weather has disappeared. I am turning my airco back into a heater. I am told that Afghanistan advertises itself as the country with 300 days of sun. Under other circumstances this might have attracted tourists. I think at least half of the sun-less days have been used up already over the last month. the only thing that tells us spring is here are the rose buds that are popping and the tiny grape bunches already visible on the vines, growing bigger each day.

The challenge of coaching my Afghan colleagues in using a very well calibrated and researched set of facilitator notes is that I cannot improvise – as much as I like to do that, and often have to do this. This is the contradiction that I experience wherever I go. It’s much like learning to dance. You first have to learn the steps and why the steps go in this order and not that order. Only when you have internalized the steps, so they become automatic and don’t require conscious thought, can you start to improvise and embroider on the material. This is difficult for me because I have to model sticking to the notes yet I know them so well that I tend to do a lot of embroidery in response to the particular needs and realities of the team. So I end up asking people to ‘do as I say’ rather than ‘do as I do.’

We follow a cow path this morning in our session. There is some logic to it since it leads to a desired endpoint but otherwise it winds this way and that. Dr. Ali, bless his heart, keeps bringing in the young women trainers. It is like a kind of inoculation against women power – if you put women up front enough the men get used to it and the sharp edges wear off.

They teach, among other things, Steven Covey’s circle of influence. It’s a popular exercise all over the world and especially here. In our notes we end with a quote that is, allegedly, from Reinhard Niebuhr about knowing the difference between the things you can do something about and those you cannot. In the middle of the exercise someone stands up and invokes (in Dari) the name of God. What follows after that sounds like a recitation from the Holy Koran. I am puzzled and a translator is sent my way. I was right. The verse translates, loosely, like this: when a problem is too big, something you can neither control nor influence, then you can leave it to God. I am trying to reconcile Covey, Niebuhr and God but have a hard time getting my head around these three.

We end the teambuilding retreat with the usual take-out lunch, always with too much bread and too much meat and/or chicken. We are served cans of Kuka Kula. I sit next to the health promotion director and he tells me that the Kuka Kula people take nice Afghan spring water and turn it into unhealthy soft drinks eagerly consumed by people used to drinking water or tea.

He has a tough job: supporting some good old habits (tea drinking) and unlearning some bad ones (spitting) and teaching the discipline of hand washing and personal hygiene aside from the nutrition, child health and maternal health behavior change communications. We, that is the women in the room, have recruited him, our first male, to be part of a coalition that has just developed its vision for a more healthy ministry of health (clean, smoke free) and a measurable result: 4 clean female toilets in the main MOPH building by December 2009.

I challenge the two young women trainers to take the lead on this initiative. At first they say it cannot be done and I question them about stopping before they have even started. Everyone gets very busy telling me why it is ludicrous to even try. It’s a perfect set up for talking about leadership. People do want to be leaders but they don’t want to change things, or don’t think they can. We use the challenge model tool that we are teaching to everyone here.

I challenge the two young women trainers to take the lead on this initiative. At first they say it cannot be done and I question them about stopping before they have even started. Everyone gets very busy telling me why it is ludicrous to even try. It’s a perfect set up for talking about leadership. People do want to be leaders but they don’t want to change things, or don’t think they can. We use the challenge model tool that we are teaching to everyone here.

Today was the last day of the various retreats in the basement of the ministry of health. One more piece of work that is externally focused happens on Thursday and after that my focus will shift to capacity strengthening in management and leadership within the project.

They discover more mistakes in the Dari flipcharts they prepared and giggle some more. I admire their resilience – they are pioneers for their sex. I ask a male colleague who has been observing with me, and occasionally translating, how big a barrier these women are trying to break through. He tells me proudly that having younger women teach older and senior males is OK in his department. It is quite an accomplishment considering that only a decade ago this would have been unthinkable.

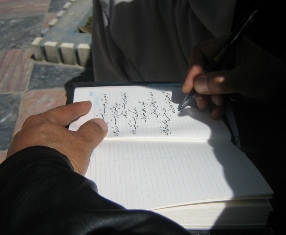

They discover more mistakes in the Dari flipcharts they prepared and giggle some more. I admire their resilience – they are pioneers for their sex. I ask a male colleague who has been observing with me, and occasionally translating, how big a barrier these women are trying to break through. He tells me proudly that having younger women teach older and senior males is OK in his department. It is quite an accomplishment considering that only a decade ago this would have been unthinkable. On our way out of the ministry we run into a man who is the son of a famous Afghan poet, and the brother of another, both named Mushda. We ask him about a poem that we can use in the sessions with the senior leaders that will help raise spirits and speak of unity and collaboration. He immediately starts to pen, in beautiful handwriting, in Ali’s diary, a poem that his father wrote 50 years ago about unity between Sunni and Shiites, between Pasthuns and Hazaras. As we walk out of the heavily barricaded ministry compound onto the street I ponder this extraordinary encounter with poetry right in the middle of the ministry’s flowering courtyard.

On our way out of the ministry we run into a man who is the son of a famous Afghan poet, and the brother of another, both named Mushda. We ask him about a poem that we can use in the sessions with the senior leaders that will help raise spirits and speak of unity and collaboration. He immediately starts to pen, in beautiful handwriting, in Ali’s diary, a poem that his father wrote 50 years ago about unity between Sunni and Shiites, between Pasthuns and Hazaras. As we walk out of the heavily barricaded ministry compound onto the street I ponder this extraordinary encounter with poetry right in the middle of the ministry’s flowering courtyard. Zelaikha lives in a high rise complex that is visible for miles – several multistory apartments with a bright red roof on top amidst colorless one story mud brick hovels built by people coming in to the city from the rural areas. Eventually these mud brick dwellings will be demolished and the people pushed further out onto the slopes of surrounding mountains, to make place for more of the high rises.

Zelaikha lives in a high rise complex that is visible for miles – several multistory apartments with a bright red roof on top amidst colorless one story mud brick hovels built by people coming in to the city from the rural areas. Eventually these mud brick dwellings will be demolished and the people pushed further out onto the slopes of surrounding mountains, to make place for more of the high rises.

Recent Comments